Hamid Zarei

Comprehensive Policy Report – August 12, 2025

1) Executive Summary

This report connects the Amman and Paris diplomatic tracks on Syria and assesses Türkiye and key Arab states’ stances in light of US and EU involvement. The Amman track focuses on immediate stabilization in Suwayda and early reconstruction; the Paris track targets national-level political transition and de-escalation (including U.S.-mediated outreach to Israel). Türkiye prioritizes countering Kurdish autonomy and border security; Arab states emphasize reintegration of Syria into the Arab sphere and leveraging reconstruction to limit Iranian influence. The US aims to sustain de-escalation and prevent an ISIS resurgence while shaping the transition; the EU (led by France) seeks a coordinated political framework and sanctions policy review to unlock reconstruction.

2) Timeline & Factual Anchors (July–August 2025)

• Jul 24–25, Paris: U.S.-mediated talks; Syrian, U.S., and French officials hold ‘frank’ discussions on Syria’s transition and de-escalation.

• Aug 9, Paris: Reports that Damascus will not attend meetings with the SDF in Paris, casting doubt on integration talks.

• Aug 12, Amman: Syria, the U.S., and Jordan agree to work toward a lasting truce in Suwayda and discuss reconstruction; formation of a working group reported.

• Context: Continued scrutiny over violence in Suwayda; reconstruction needs estimated in the hundreds of billions; EU sanctions debate and French advocacy for review earlier in 2025.

3) The Two-Track Architecture

Amman Track – ‘Stabilize the Ground’: Focused on consolidating the Suwayda ceasefire, minority protection, humanitarian access, and early recovery. Objective is to demonstrate tangible stability to build political confidence.

Paris Track – ‘Build the Structure’: Focused on national-level political transition, inclusion/normalization issues, de-escalation (including U.S.-mediated contacts), and the question of integrating autonomous forces (e.g., SDF) into state structures.

4) How Amman Feeds Paris (and Vice Versa)

• Grounded Legitimacy: Local stability successes in Suwayda (Amman) provide credibility for national transition claims (Paris).

• Sequencing: Security guarantees and humanitarian relief precede constitutional and force-integration questions.

• Working Mechanisms: A trilateral working group (Amman) can supply data/benchmarks to Paris negotiators.

• Confidence-Building: Reduced violence and aid access lower the political cost of compromise in Paris.

5) Türkiye and Arab States: Core Positions

Türkiye:

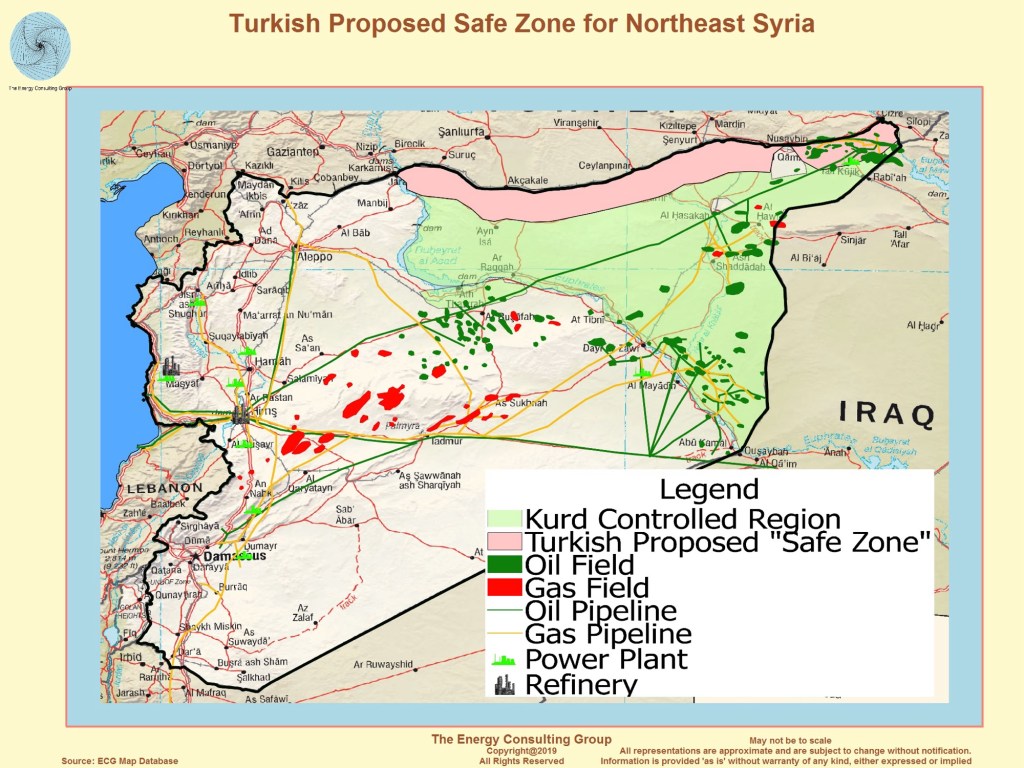

• Red lines on Kurdish autonomy/SDF; insistence on border security; preference for rapid deconfliction arrangements.

• Willingness to trade economic openings for security concessions; coordination/deconfliction with Russia continues; NATO ties constrain options.

Arab States (Jordan, Saudi Arabia, UAE, Egypt – positions vary):

• Reintegration of Syria into Arab structures to dilute extra-regional leverage; preference for sovereign control and territorial integrity.

• Use of reconstruction finance as leverage for security reforms and political inclusion; priority on southern stabilization to protect borders (esp. Jordan).

6) US and EU Roles

United States:

• Mediation on de-escalation (including reported Israel–Syria humanitarian discussions linked to Suwayda).

• Security focus on ISIS containment and preventing regional spillover; support for structured political transition.

European Union / France:

• Paris diplomacy to align political transition with European consensus; debate on calibrating sanctions to enable humanitarian and early recovery funding.

• Interest in predictable security to unlock EU instruments and private investment, contingent on governance benchmarks.

7) Convergence / Divergence Map

Convergences:

• All parties prefer de-escalation in Suwayda; preventing ISIS resurgence; enabling humanitarian access; and a sovereign, territorially unified Syria.

• Broad interest in unlocking reconstruction subject to political/security benchmarks.

Frictions:

• Türkiye vs. decentralization models involving SDF; timelines for Turkish military footprint normalization.

• Arab capitals’ appetite for political normalization vs. conditions to curtail external (especially Iranian) influence.

• EU/US sanctions calibration vs. demands for faster reconstruction inflows from regional investors.

8) Scenarios (2025–2027)

A) Managed Pragmatism (Most Likely):

Amman quietly expands to other hotspots; Paris locks in a stepwise political framework; Türkiye accepts limited local governance arrangements with strict security guarantees; Arab funders back pilot reconstruction tied to verifiable stability metrics.

B) Transactional Fragmentation:

Security holds in some zones but political integration stalls; episodic Turkish–SDF tensions spike; EU sanctions remain tight, constraining reconstruction finance.

C) Compact Breakthrough (Low Probability, High Impact):

A broad agreement aligns decentralization, force integration, and sanctions relief; major reconstruction flows begin with robust monitoring.

9) Policy Options & Recommendations

For Amman Track Stakeholders (Jordan–Syria–US):

• Formalize the working group with public metrics (aid access hours, incident counts, detainee processing times).

• Build a Suwayda Stabilization Package: localized policing support, hospital protection, Druze community liaisons, and monitored corridors.

For Paris Track Stakeholders (Syria–US–France/EU):

• Sequence political steps to concrete field benchmarks from Amman; de-risk early sanctions calibration via a humanitarian carve-out registry.

• Launch an Integration Dialogue: explore security-sector models for phased incorporation of autonomous forces under unified command.

For Türkiye and Arab States:

• Establish a Türkiye–Arab consultative forum on Syria to harmonize border security, refugee return standards, and counter-smuggling.

• Agree on a ‘Decentralization-with-Guardrails’ framework that preserves sovereignty while addressing local governance needs.

For US/EU:

• Sustain mediation (including any humanitarian corridor arrangements) and tie assistance to measurable stability outcomes.

• Prepare a sanctions roadmap linked to verifiable de-escalation and protection-of-civilians commitments.

Annex: Reference Notes

• AP: Syria, US and Jordan commit to lasting truce in wake of Suwayda clashes (Aug 12, 2025).

• Reuters: Syria–US–France ‘frank’ talks in Paris on transition (Jul 25, 2025).

• Reuters: Syrian–Israeli de-escalation discussion in Paris (Jul 24, 2025).

• Xinhua: Amman trilateral on Suwayda ceasefire (Aug 12–13, 2025).

• Reuters: Damascus says it won’t attend Paris meetings with SDF (Aug 9, 2025).

• Reuters: Macron/EU sanctions review remarks (May 7, 2025).